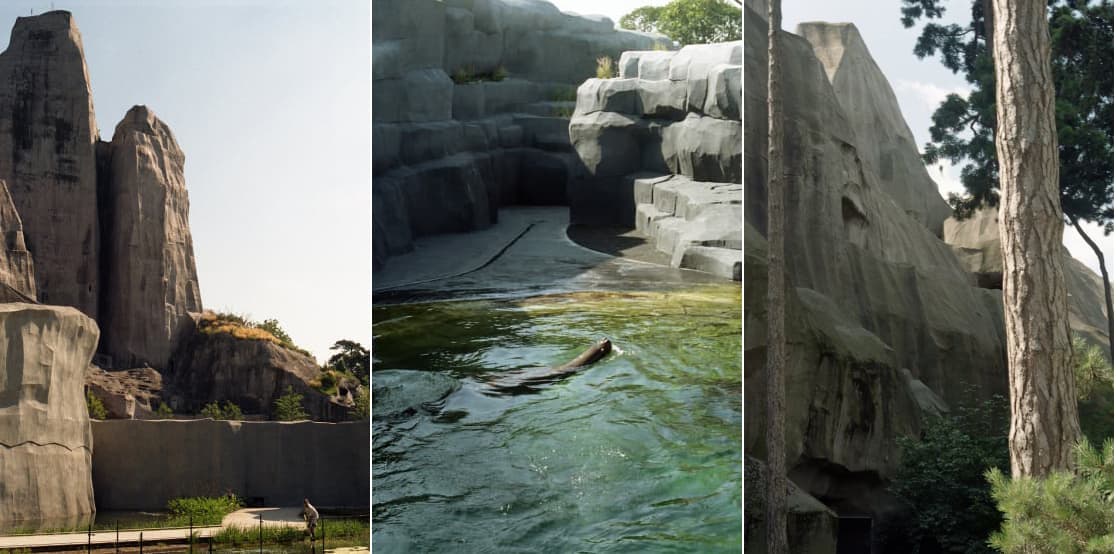

In April 2014 Parc Zoologique de Paris was reopened after a six-year development period. The park is divided into five ‘ecosystems’, with species sharing enclosures where possible. The giant, vertical boulder, the manmade ‘Grand Rocher’, is the only part of the original site to remain after the refurbishment.

In April 2014 Parc Zoologique de Paris was reopened after a six-year development period. The park is divided into five ‘ecosystems’, with species sharing enclosures where possible. The giant, vertical boulder, the manmade ‘Grand Rocher’, is the only part of the original site to remain after the refurbishment.

Parc Zoologique’s manmade rocks and landscaping act ‘as a trompe l’oeil’ to mask the captivity of the animals. Rothfels proposes that advanced replications of nature in zoos mean that the animals contained within ‘face a much more difficult time in finding a voice with which to query their audience’.

With the shrinking wilderness having lost much of its sublime and awesome meaning, zoos are required to become curators of the wild. This is a disturbing prospect, not only because the key meaning of wilderness is that it is not made by people, but also because aims to engage visitors through exploration are thus rendered ‘nonsensical’: within a manmade landscape, visitors can’t discover anything other than that which has been prepared for them.

With the shrinking wilderness having lost much of its sublime and awesome meaning, zoos are required to become curators of the wild. This is a disturbing prospect, not only because the key meaning of wilderness is that it is not made by people, but also because aims to engage visitors through exploration are thus rendered ‘nonsensical’: within a manmade landscape, visitors can’t discover anything other than that which has been prepared for them.

On arriving at the Parc Zoologique de Paris, I found the newly planted landscape almost barren in places. The concrete rocks were painted to fade from dark to light. In the early morning, staff used rakes to hook out long green swathes of waterweed from the ‘Sahel Sudan’ prairie, in the shadow of the Grand Rocher. The sculpted concrete rockwork cascaded down as giant blue-grey boulders that appeared almost digital in their geometricity. Ostriches and kudu stood peacefully grazing in the near-distance, kept away from the flat, wide walkway by almost-invisible wire fencing. In the golden early-morning light, the scene resembled a pastoral oil painting – with figures working the land, dwarfed and humbled by the surrounding landscape, animals as part of the receding view, and a pathway tapering around a corner to invite contemplative exploration – except the subject was eerily unnatural. The workers were part of the landscape, a tamed, urban-natural space, completely orchestrated. It was strangely peaceful, like the beginning of an epic theatre production.

Hancocks, David, 1971. Animals and Architecture. London: Hugh Evelyn Limited.

Mullan, Bob & Marvin, Garry, 1999. Zoo Culture. Urbana & Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Rothfels, Nigel, 2002. Savages and Beasts: The Birth of the Modern Zoo. Baltimore & London: The John Hopkins University Press.

Tuan, Yi-Fu, 1990. Topophila: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values. New York & Chichester: Colombia University Press Morningside Edition.

Willsher, Kim, 2014. ‘Paris zoo to reopen after a €133m revamp and Grand Rocher facelift‘ [online]. Guardian.