Elephants are once exotic and familiar: they can be trained to give rides, perform and interact with people closely due to their mental capabilities. Originally London Zoo housed their elephants in a whimsical cottage, and much later, in 1939, elephants were kept in Lubetkin’s relatively tiny Gorilla House. Before the practice was stopped in the early 1960s, elephants were exercised through giving rides to visitors. It was believed that ‘[a]n unreliable elephant is a most unproductive investment for any Zoological society’.

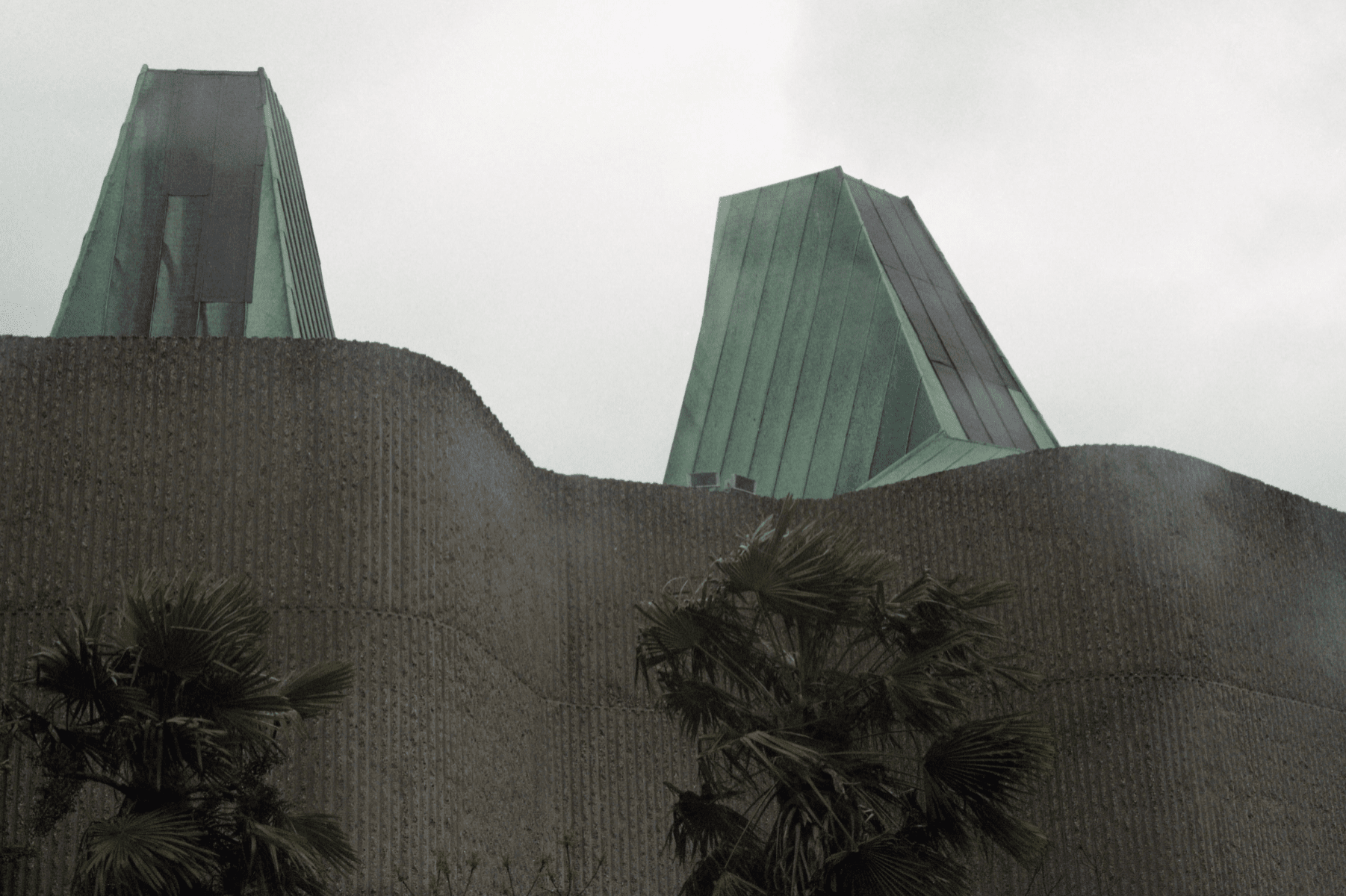

A new home was built as part of 1958’s ‘New Zoo’ redevelopment plan. The Elephant & Rhino Pavilion, or Casson Pavilion, ‘seemed to attempt to create an idea or abstraction of “nature” without resembling anything that could actually be seen in nature’: its most distinctive design feature was the green copper silos which rise ‘like a clump of pachyderms with their heads together’. The rough concrete coating of the building resembles an elephant’s skin and is tough enough to prevent the animals from damaging the fabric.

Despite winning the 1965 RIBA ‘Best Building in London’ award, the Pavilion faced a multitude of criticisms. Hancocks noted economic cuts resulted in diminished paddocks at the expense of the animals’ needs, rather than the height of the building being curtailed. The tall space also reputedly causes swirls of damp air. Casson himself noted zoo enclosure plants are often destroyed or eaten, or harbour parasites. He also noted that elephants: ‘behave in certain ways which make them not the easiest creature to deal with – they can even pick locks with their trunks. Everything must be out of their reach’.

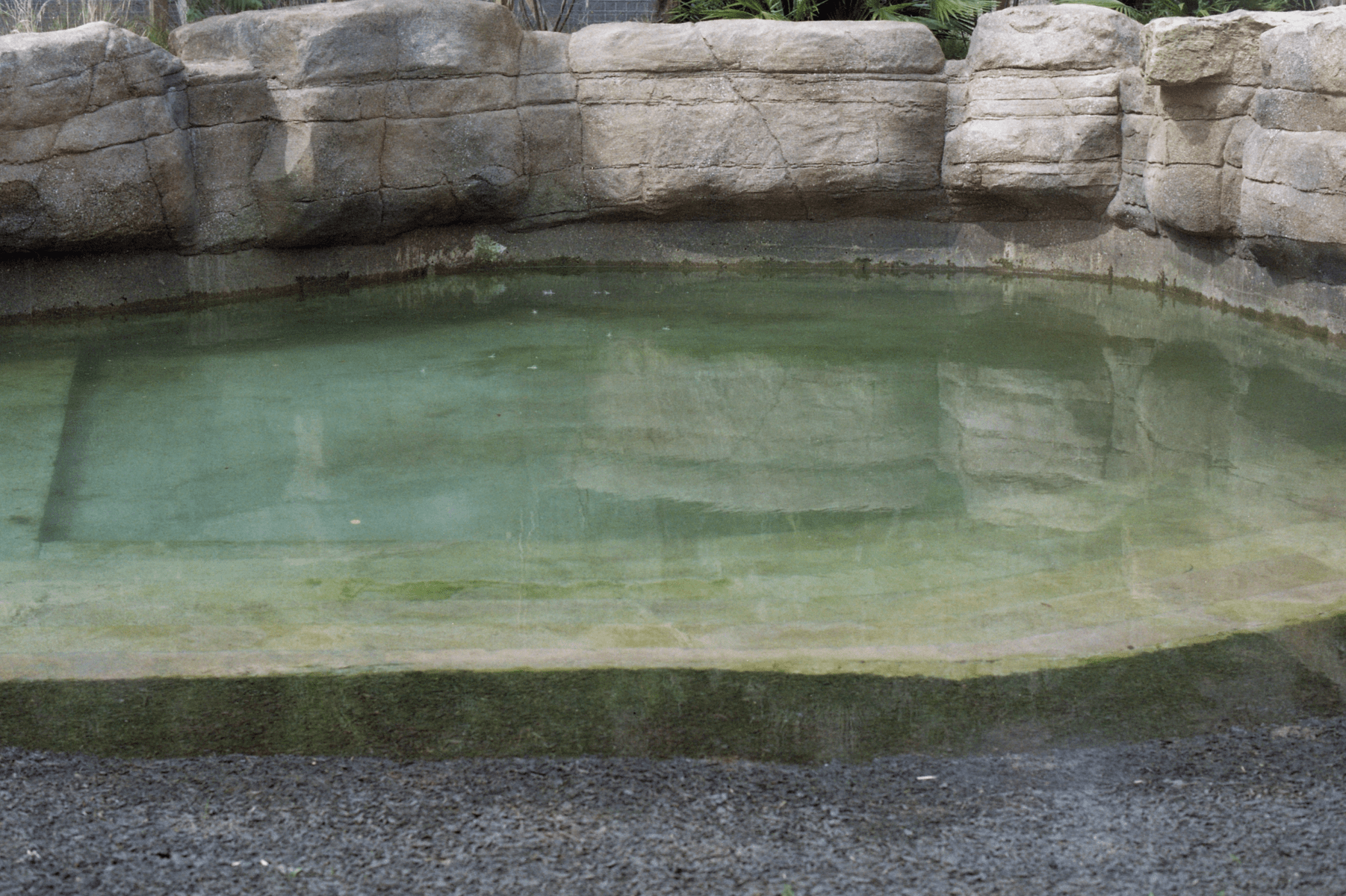

Early images of the Pavilion show a bare, grey-brown yard. The Pavilion had a pool but the elephants did not make use of it until public feeding had been banned in 1968. Barrington-Johnson indicates an original pool was not big enough for adult elephants, and so a larger one was built. The paddock moat filled with detritus even after the public ban on feeding. The elephants’ own food had to be kept in the basement of the Pavilion and inconveniently hoisted upward. Overall it appears ‘the space for visitors far exceeds the narrow nooks created for the immense creatures’.

Over the next four decades, the building became host to tragedy: keeper Jim Robson was killed by an elephant. There were reports of the elephants’ physical and mental health being affected by their captivity in the Pavilion, not at least that of Pole Pole, a female African elephant. Pole Pole was originally captured in the wild (her mother killed), and gifted to the Zoo by the Kenyan government. After a period loaned to a film production company, Pole Pole was sent to live in the Casson Pavilion. She exhibited a range of health problems, including rocking and repetitive knocking against the rough walls: ‘[o]n her rump, her head, her shoulders … there are grey patches that looked chaffed… her tusks have been obliterated on the walls of her enclosure’.

The Pavilion’s layout meant it was difficult to separate individuals, and when outside, the elephants risked falling in the moat. This happened on two occasions, causing the death of one elephant, and another – named Toto – to suffer injuries that may have led to her death. Toto died inside the building, and zoo staff realised there was no way of removing her body intact through the doors of the Pavilion. A post-mortem was undertaken in the cell next to Pole Pole. An elephant’s sense of hearing and smell is apparently very advanced. Pole Pole was reputedly severely disturbed through experiencing the post-mortem of her companion, constantly walking in circles for weeks afterwards. Her health continued to deteriorate, and she led an increasingly lonely life as gradually all other elephants were moved to Whipsnade. On an attempt to move Pole Pole, she was overcome with stress and had to be put down.

Today, the Pavilion houses bearded pigs and tapirs instead of elephants. This is against protests in the press, accusing Regent’s Park’s of ‘political correctness’, and presumably against some visitor expectations: I personally overheard several visitors asking staff where they could find them, and tourist review websites such as those on Trip Advisor occasionally bemoan the lack of elephants at the site. That London Zoo was committed to move out some of its most popular animals from a large, relatively new, grade-listed building speaks of its dedication to animal welfare.

Meanwhile, The Elephant & Rhino Pavilion becomes masked by foliage and the space around the building subsumed by Tiger Territory. There are no benches directly overlooking the bearded pig or tapir enclosures. Despite its position close to the main picnic thoroughfare, the structure blends into the background. A sign by the Pavilion’s locked doors explains the Zoo now prefers ‘to create green and natural enclosures’. On my own visits, I saw the tapirs outside once: they seemed keen to get back inside. I found it difficult to imagine large crowds in the wide space around the building when elephants and rhinoceroses lived there, and difficult to think of the large creatures living in the pens after learning of Pole Pole’s distressing life.

Barrington-Johnson, J., 2005. The Zoo: The Story of London Zoo. London: Robert Hale.

BBC News, 2001. ‘Elephants leave London‘ [online].

Born Free Foundation, [no date]. ‘The Story of Pole Pole‘ [online].

Chinery, Michael, 1976. Life in the Zoo. Glasgow & London: Collins.

Gleeson, Gertrude, 1933. The Zoological Gardens. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Co.

Guillery, Peter, 1993. The Buildings of London Zoo.

Hancocks, David, 2001. A Different Nature: The Paradoxical World of Zoos and Their Uncertain Future. London: University of California Press.

Hancocks, David, 1971. Animals and Architecture. London: Hugh Evelyn Limited.

Haywood, Mark, 2012. ‘A Brief History of European Elephant Houses: From London’s Imperial Stables to Copenhagen’s Postmodern Glasshouse’ [online]. Academia.

Jenkins, Simon, 2001. ‘Save the Regent’s Park Three‘ [online]. London Evening Standard.

McKenna, Virginia, Travers, Will & Wray, Jonathan, eds, 1987. Beyond the Bars: The Zoo Dilemma. Wellingborough: Thorsons Publishing Group Ltd.

Miller, Keith, 2002. ‘Making the grade: Elephant and Rhino House, London Zoo‘ [online]. Telegraph.

Pastscape, 2007. ‘Casson Pavilion‘ [online].

Rothfels, Nigel, 2002. Representing Animals. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Tyler, Adam, 1983. ‘Elephants’ Graveyard‘ in Time Out, No.664, May 13–19 1983. Animal Aid.

Wainwright, Oliver, 2013. ‘London Zoo’s new Tiger Territory: built for the animals first, and visitors second’ [online]. Guardian.