Berthold Lubetkin and his architecture firm Tecton were commissioned to design a pool for London Zoo’s penguins in 1934. Their earlier commission resulted in a white, circular Gorilla House. Modernist design was a move toward a ‘biotechnic age’, yet Gruffudd notes that these buildings were the result of new ideas about nature and ‘experiments in harmonizing living creatures and their designed spaces’ through rational scientific enquiry. The penguin commission gave Lubetkin chance to showcase modernist design to the masses: he saw architecture as a statement of the social aims of the age to help man understand, to explain and to control his surroundings. Lubetkin undoubtedly considered the needs of the animals in the design process, yet in a way philosophically distinct from his predecessors: he rejected the naturalistic approach as ‘tokenism’. For Lubetkin, naturalistic design ‘allowed the very shy animals to hide themselves from the public gaze … while those with a taste for publicity were not able to indulge it’. The zoo was a theatre: an appropriate building would showcase the penguins’ pure ‘penguinness’.

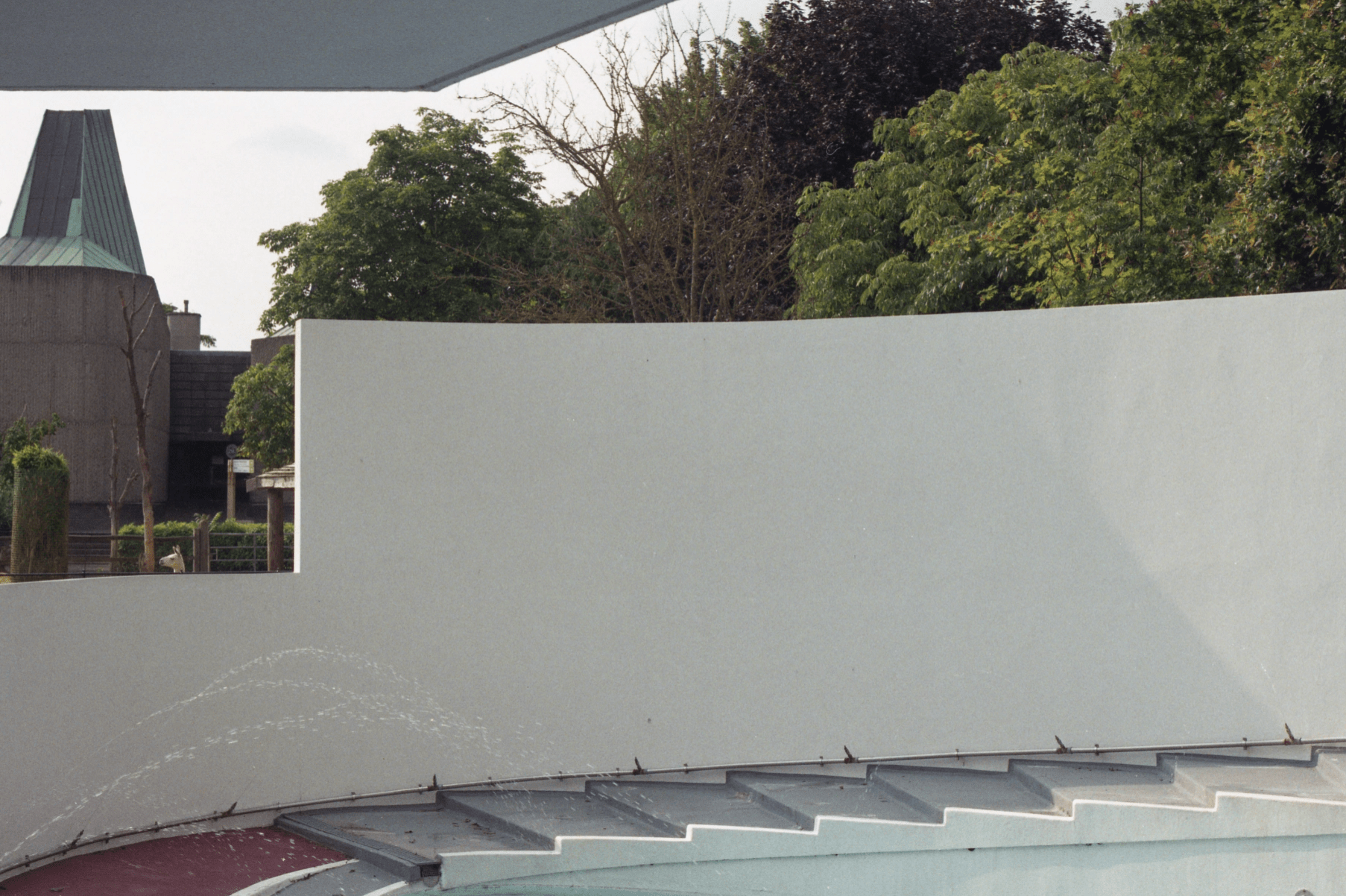

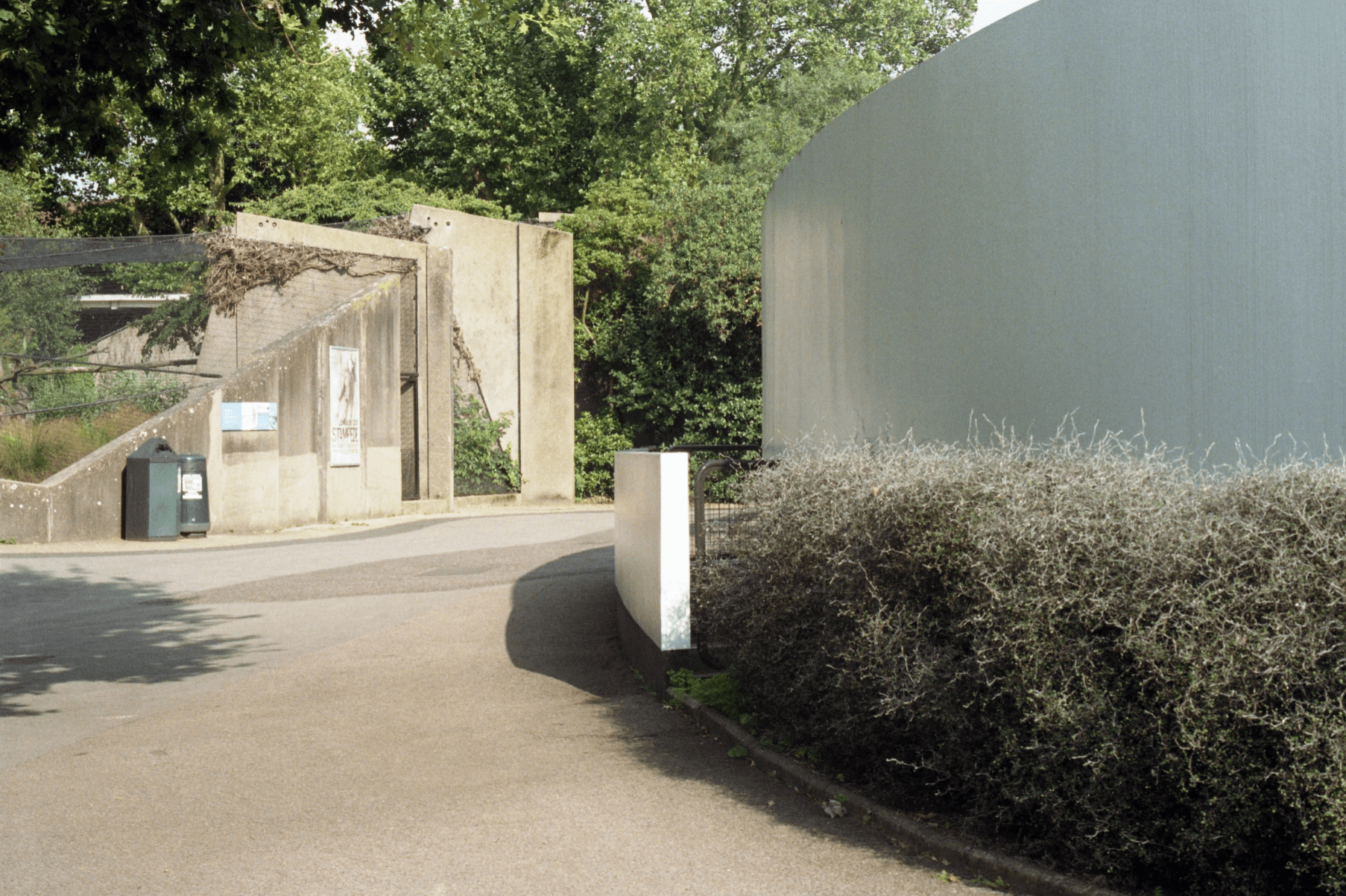

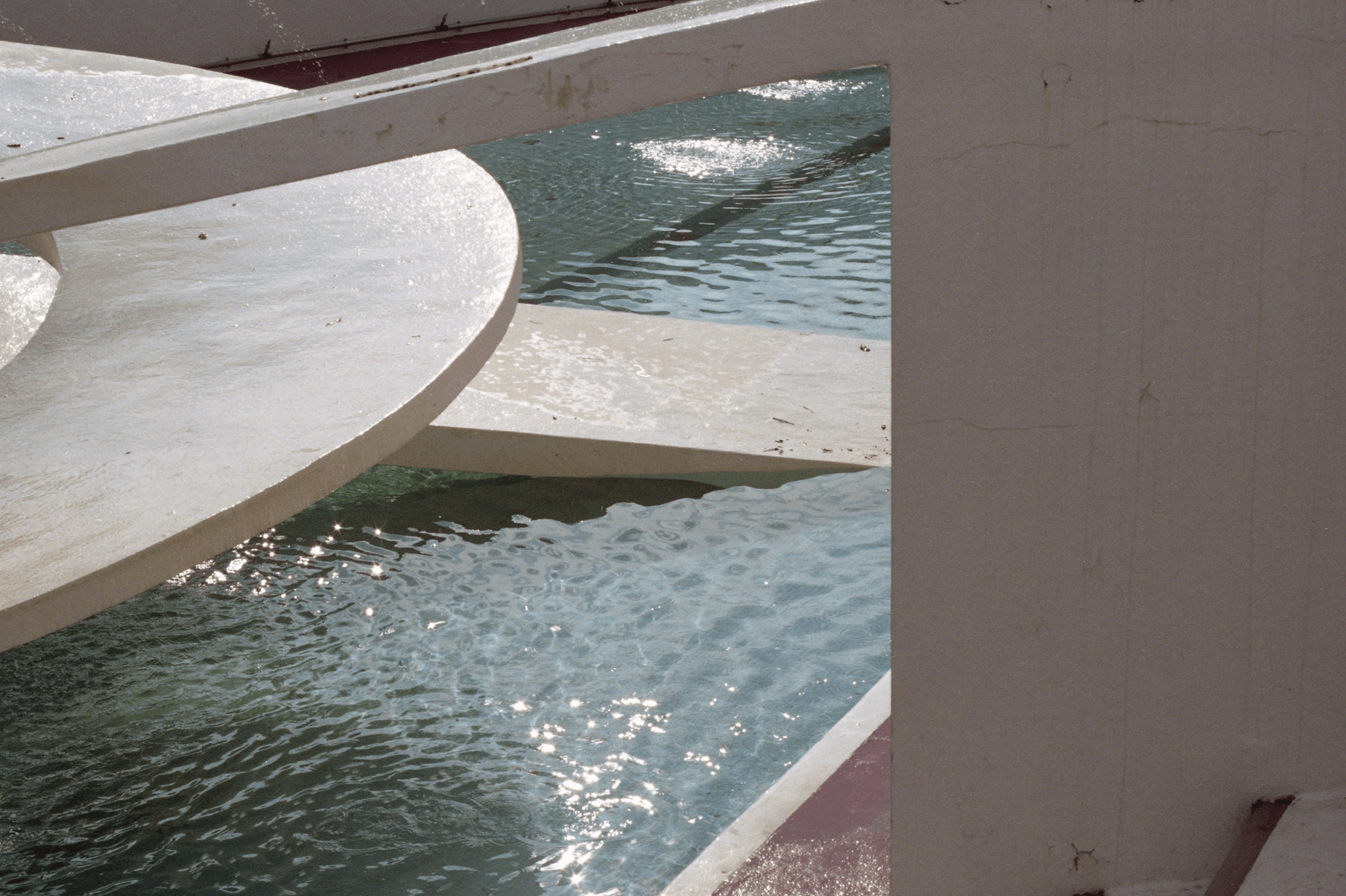

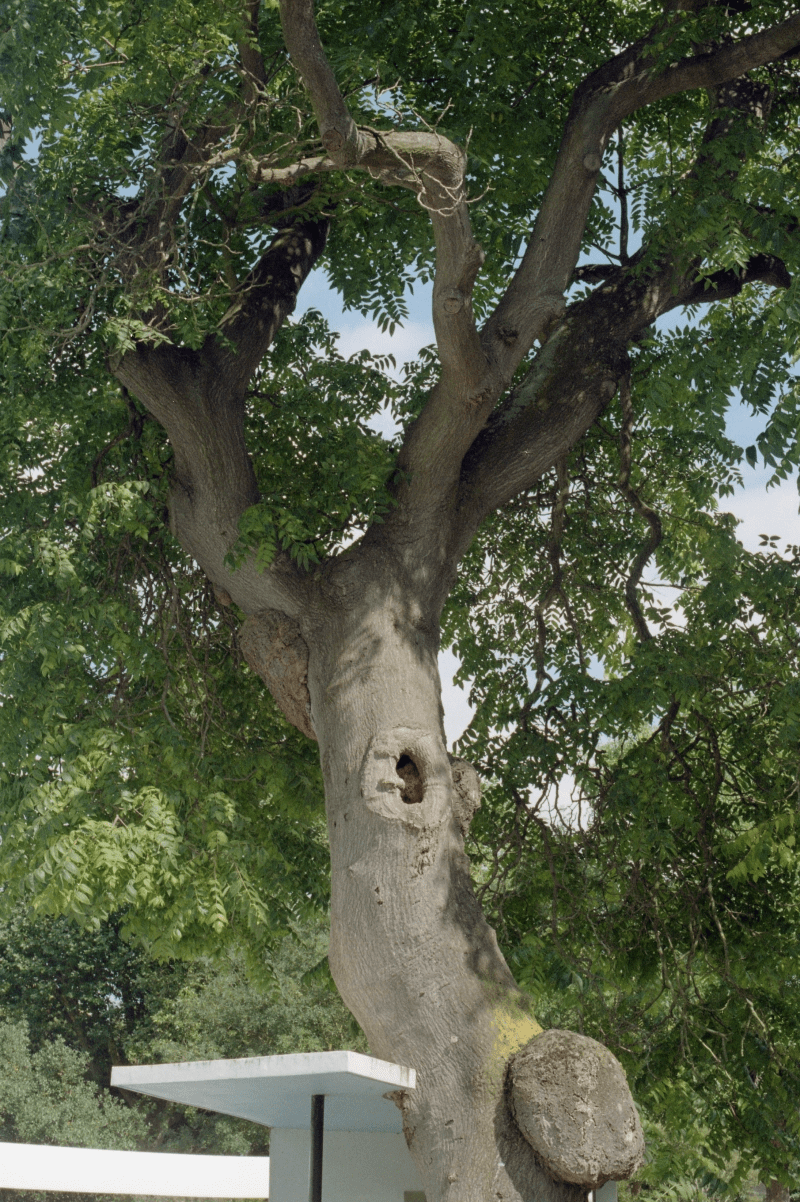

Zoogoers enjoyed leaning over the parapets to look down upon the ‘little dinner-jacketed friends’ plodding up and down the ramps, and the Pool was critically well-received. Its circular form, like an egg, meant the walls acted as a sounding board for the penguins’ calls. It also had a variety of floor surfaces to stimulate the birds and a diving pool. The nearby ailanthus tree was incorporated in Lubetkin’s plans as ‘a natural foil to his geometric abstraction’, and for practical reasons too: fallen twigs and leaves provided the penguins with nesting material. I was interested to see old photographs where the young tree had not yet needed to be accommodated by a cut-out section. The penguins bred successfully, which was believed to indicate a successful zoo building.

However, 70 years after the Pool’s creation, the penguins were moved out. A temporary relocation caused an increase in courtship behaviour. Other factors that convinced the zoo to move the penguins were that the Pool was a heat-trap in summer, the penguins’ feet hurt from the flooring and the birds couldn’t dive in the shallow water, the bright white surfaces apparently damaged the penguins’ eyes, and later species additions preferred different nesting quarters. Chinese alligators didn’t like the Pool either, even with added plants and mud – the addition of which preservationists argued was proof London Zoo ‘does not comprehend the aesthetic qualities of its best building’.

Today, the Penguin Pool is surrounded by a café’s picnic benches. Faces tend to fall when visitors find it empty. During my visits I saw many lean over the parapet and comment ‘there’s nothing in here!’ or ‘what’s in here?’ – one visitor even asserted the Pool would be ‘where the penguins do their show later’, having ignored the large explanatory signs. The ailanthus’ fallen leaves and twigs lie in the fountain, sometimes along with the odd plastic bottle or other piece of litter.

I think the building does convey an ambiguous nature/culture binary, especially incorporating the tree: afternoon sun casts a silhouette of leaves on the plain walls of the pool, like flocked wallpaper. Lubetkin’s creation appears like a bright, white space station, indicating the future is somewhere nice to be. I can concur, when the Pool is in warm afternoon light, but in cloudy weather, it seems grey, cold and uncomfortable. I heard children shout ‘swimming pool!’ as they approach: the drops echoing on smooth painted concrete is reminiscent of an outdoor lido, memories of which give me goose pimples in cool air. The sound of the water is amplified, yet soothing, and perhaps masks noise for the birds of prey housed nearby.

Allan, John, 2002. Berthold Lubetkin. London: Merrell.

Allan, John, 1992. Berthold Lubetkin: Architecture and the Tradition of Progress. London: RIBA Publications Ltd.

Anderson, Kay, 1998. ‘Animals, Science and Spectacle in the City’ in Wolch, Jennifer & Emel, Jody, eds, 1998. Animal Geographies: Place, Politics, and Identity in the Nature-Culture Borderlands. London: Verso, pp.27–50.

Avanti Architechts, [no date]. ‘Penguin Pool, London Zoo’ [online].

British Pathé, 1939. ‘Penguins‘ [online].

Building Design, 2004. ‘Lubetkin pool was penguin turn-off’ [online].

Coe, Peter & Reading, Michael, 1981. Lubetkin and Tecton: Architecture and Social Commitment. London: The Arts Council of Great Britain & Bristol: The University of Bristol.

Glancey, Jonathan, 2004. ‘Penguins moved from listed pool’ [online]. Guardian.

Gruffudd, Pyrs, 2000. ‘Biological Cultivation: Lubetkin’s Modernism at London Zoo in the 1930s’ in Philo, Chris & Wilbert, Chris, eds, 2000. Animal Spaces, Beastly Places: New Geographies of Human-Animal Relations. Oxon: Routledge, pp.222–242.

Guillery, Peter, 1993. The Buildings of London Zoo.

Hediger, H., 1964. Wild Animals in Captivity. New York: Dover Publications Inc.

Wainwright, Oliver, 2013. ‘London Zoo’s new Tiger Territory: built for the animals first, and visitors second‘ [online]. Guardian.